In Conversation

Darius Himes, International Head of Photographs at Christie’s, discusses the creation of Light Years with Dmitri Cherniak and Daniel Hug, from the Estate of László Moholy-Nagy.

Darius speaks to Dmitri Cherniak

Darius Himes: In which ways do you feel the work of László Moholy-Nagy offered a leaping point for your creative exploration? How did you set parameters for this work in the code that would create a dialogue with his work?

Dmitri Cherniak: Moholy-Nagy is a pioneering artist, thinker, and educator that I admired well before Light Years was conceived, so when I was given the opportunity to dig into his archives and writings I jumped at the opportunity.

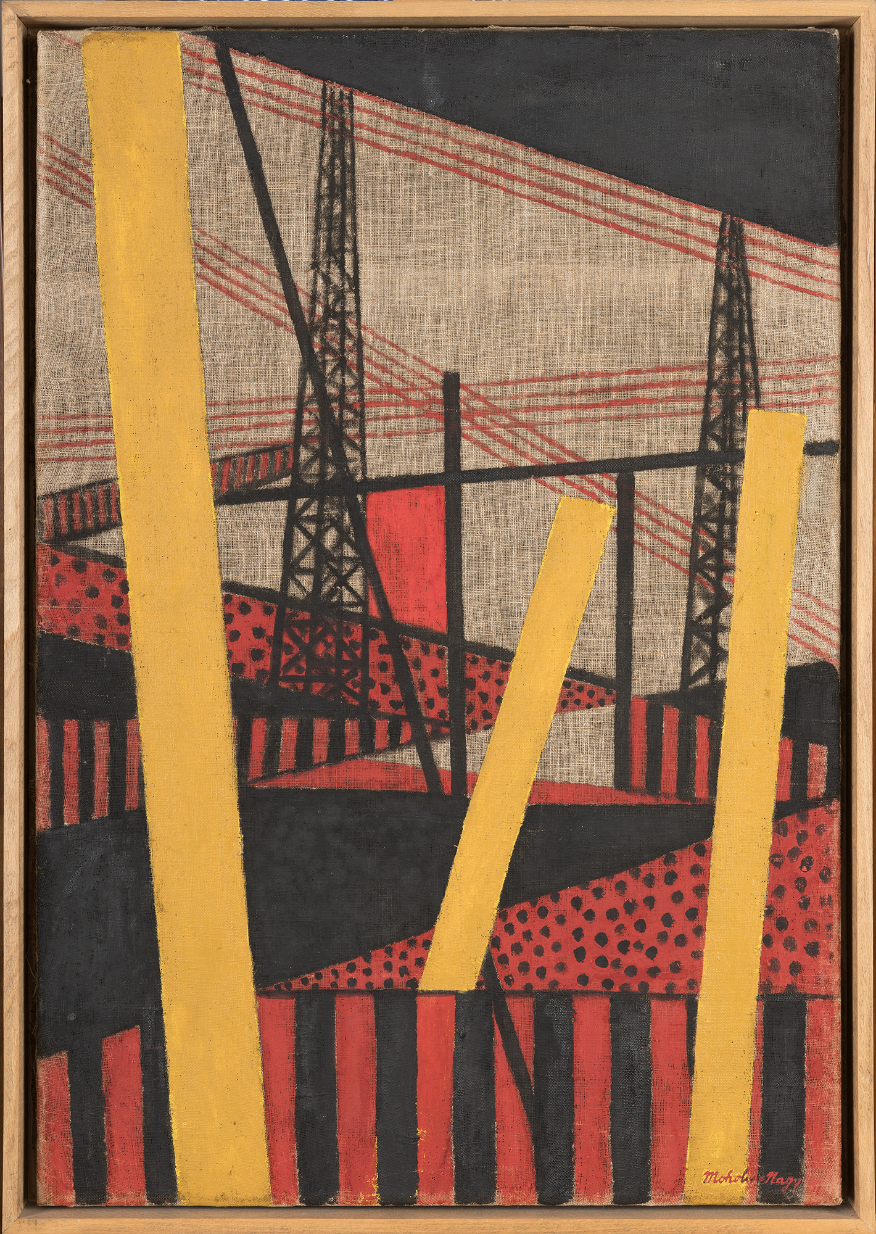

Even in his early figurative works, Moholy-Nagy highlighted the technological advances of his day front and center - in particular train tracks and telephone wires that ran through the fields near his home (Crossing Diagonals, 1925 and Radio and Railway Landscape, 1919-1920)

The use of train tracks and telephone wires felt rather symbolic to me, connecting Moholy-Nagy to my own generative art practice through time and space. The core of the algorithm is built around creating train track-like segments that shift in perspective such that they can also appear as telephone poles and wires.

Dmitri Cherniak

I used a number of parameters to help dive into this aesthetic: from the number of track segments that may show up on the screen, the perspective shift parameters, parameters for drawing lines, and even the frequency of different kinds of segments between each railroad tie/truss.

The progression to the final works you see was as much about my discovery of the visuals made possible by parameterizing the system as it was about programming the underlying algorithm.

HIMES: What elements of Light Years would you consider photographic, if any?

CHERNIAK: Light Years is very much an homage to the photogram as a medium, but with a digitally native twist. I am creating “photographs” outside of the camera body, partially using an autonomous system programmed by code, and partially using a hand curated and polished analog photographic development process.

I knew from the start that if I didn’t find a way to tie together the digital nature of my work to the analog photographic process I would be doing a disservice to Moholy-Nagy.

I would consider the final work as both generative and photographic, however, there are definitely some elements I added in along the process to try to make sure the works would shine as silver gelatin prints. For example, the color inversions, the layering of increasingly opaque forms to create an appearance of depth, and the addition of grain was very much inspired by the textures that are possible in black and white photography.

HIMES: Can you discuss the relationship of negative and positive space in this work? In photographic terms, this dichotomy is intrinsic in the medium. How did this contrast affect the way you created the code?

CHERNIAK: As it was designed to be a “photogram,” from the start I knew it would very much be a study of both light and dark. When making art with code there is quite a lot of nuance with black and white, as pure black or #000000 and pure white #ffffff are often quite jarring and unnatural to the eye, and also can cause unfortunate banding artifacts in the film development process, so I spent a lot of time considering how to make sure the print would come out nicely.

In terms of how negative and positive space are created, I was able to play around with the density of elements “printed” to the canvas and how intensely or frequently they might be warped. As I am able to scroll through thousands of outputs rather quickly, I could play around with parameters and outputs until I found works that I felt aesthetically were somewhat balanced or interesting. The inversions were added afterwards and highlighted the structure and form of the elements.

HIMES: You’ve explored different elemental forms in your different bodies of work (lines, triangles, squares, circles), especially the idea of the circle. Can you tell us about the significance of that form in your work? Is there a symbolism that can be articulated from its use in your art?

CHERNIAK: I thought about the circle in a few ways in this project. The first as a spotlight, something that shines and draws attention, or in the inverse, a dark hole, something that draws you in - circular beams of light or dark are powerful forces.

Regardless of its relation to light, the circle’s curvature also adds a calmness to the rigid geometric forms. You can see how Moholy-Nagy used the circle in his constructivist works and his overhead photography from the Berlin Radio Tower to bring focus and clarity to otherwise rigid forms.

Finally, the groupings of circles reminded me of the shadows and light beams cast from Moholy-Nagy’s Light Prop for an Electric Stage, 1930.

HIMES: As you’re working on a project, and the code outputs a myriad of variations, how do you guide and manipulate the “output” so that it fulfills your vision.

CHERNIAK: This is the hardest part of what I do. I like to think of it as an iterative and interactive process. Ultimately I develop systems that allow me to reproduce works I have generated previously so I am not afraid to go down different paths and explore. I also program in parameters for almost any element I introduce to make sure I can swing between extremes and explore new possibilities I might not otherwise have considered.

I am empowered by randomness, speed and reproducibility, which lets me dig into the visual “space” of an aesthetic concept in a way that you can’t when working in a strictly physical medium.

Dmitri Cherniak

HIMES: In knowing that you were going to create analogue prints from the digital outputs, what new possibilities or challenges did you find within the way you engineered and transformed the code?

CHERNIAK: The process was to create outputs at a certain resolution, review and prepare those outputs, print those outputs to film negatives, and then develop those film negatives as silver gelatin prints at a certain size.

The transition between each of those steps has specific and nuanced issues I had to account for from both logistical and technical standpoints – and that doesn’t even account for any kind of creative or artistic challenges.

I was fortunate to be able to work with some of the best photo printers in the world who helped guide me through this process, and in particular were able to help with the most difficult parts of turning digital into analog.

Dmitri Cherniak

HIMES: What did you find conceptually valuable about creating the final NFTs from the scanned analogue negatives used to create the silver gelatin prints?

CHERNIAK: As a generative artist, my work tends to be natively digital: the essence of my work is in the code and its execution of an output. In this case however, the generative output was printed to a film negative, not a screen or digital display, so I felt capturing the scan of that film negative was in fact the best way to capture the digital essence of this work.

Sure it would be possible to use a raw digital file as the NFT, but you miss out on the analog artifacts that make each output impossible to recreate.

HIMES: Code, as you mentioned in the documentary, is used mostly for commercial endeavors, or even for control. How does reverting it to create visual explorations make you feel?

CHERNIAK: It makes me feel empowered as a human being. As a technologist, I have spent a lot of my life fascinated by the creative energy required to solve problems using automation, while less technologically savvy observers might think of it as the exact opposite - a robotic, boring and rote procedure.

Because coding has been mostly thought of as an economic tool - a way to get a job, or save money and time - the general public has almost no understanding of coding as a tool of expression.

Darius speaks to Daniel Hug from the Estate of László Moholy-Nagy

Darius Himes: Moholy-Nagy was an innovator and experimenter throughout his life. What was the overarching philosophy behind his experimentation?

Daniel Hug: Moholy's entire oeuvre is both holistic and pedagogical, centred in pursuit of improvement of the social environment to benefit the individual. It concerns the education of the senses through art and reflects biologically-based educational theories of the early 20th century German Schulreformbewegung [school reform movement] played out in the Youth Movement.

"The human construct is the synthesis of all its functional apparatuses, i.e. man will be most perfect in his own time if the functional apparatuses of which he is composed his cells as well as the most sophisticated organs are conscious and trained to the limit of their capacity.”

László Moholy-Nagy

.jpeg)

HIMES: His use of photography was unscripted and without rules; he appeared to use photography as a means towards other ends. Was this true of his work in other mediums?

HUG: Experimentation and investigation of new technologies were always at the root of his artistic practice. For example, the full significance of Moholy-Nagy’s photograms (camera-less photography) became apparent only in the early 1930s, when he created a machine for setting shadows in motion. Moholy’s Light Prop for an Electric Stage, which incorporates several motorised grates rotating in tandem. Their interaction results in complex flickerings of light that are astonishingly dynamic. Produced in collaboration with German electrical company AEG, the technology was intended to optically stimulate audiences in theatres and at festivals: a truly populist manifestation of abstract art that moved abstraction into another dimension.

In light of this work, Moholy-Nagy produced Ein Lichtspiel schwarz weiss grau (Light-Play: Black-White-Gray), a truly mesmerising film.

In 1933, László Moholy-Nagy began experimenting with silberit, a specialised aluminium developed for aeroplanes. He was attracted to silberit for its extreme reflectiveness. Using the metal as a background for abstract paintings, he made his pigments appear to levitate. Around the same time, Moholy-Nagy tested the optical effect of plastics such as Rhodoid, Galalith and Trolit, and applied pigments with industrial equipment including a spray gun and airbrush.

HIMES: At times he used a camera; at other times he worked camera-less. Was he trying to achieve different things with these different techniques?

%2C%E2%80%9D%201929%2C%20gelatin%20silver%20print.%20George%20Eastman%20Museum%2C%20Rochester%2C%20New%20York.jpeg)

HUG: Moholy-Nagy believed that the medium of photography will dramatically change the world.

The different techniques achieve different formal properties and effects, which allow education of the senses.

[Moholy-Nagy’s] famous quote resonates with our contemporary world: "The illiterate of the future will be the person ignorant of the use of the camera as well as the pen.”

Daniel Hug

HIMES: The role of shapes and forms, such as lines and circles, in art can be about conveying a message through abstract forms. Was Moholy-Nagy interested in building a new language for the visual arts?

HUG: Moholy believed that geometry is inherent in nature. Apart from the intensity of his colour awareness, the richness of his nature imagery and organic metaphors are indicative of the early works. Therefore, he may have found his new language in Constructivism. Moholy's late work was still both biomorphic and abstract, and, as with Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Hans Arp, this style visualizes biocentrism. In Chicago, Moholy's stress on ergonomic design and his increasing concern with ecological issues, "the incoherent use of our rich resources” underlines this

HIMES: What are the areas of overlap and synergy that you see between Dmitri and László's work?

HUG: Dmitri's work diverges from a similar starting point. We believe Dmitri and Moholy-Nagy have a common vision for a future where technology can advance our creative and cultural potential.

HIMES: How does it make you feel when you look at the images Dmitri produced for the Light Years project?

HUG: We are impressed by Dmitri’s integration of Moholy-Nagy motifs into his own creations. Contextualizing the legacy of Moholy-Nagy’s life’s achievements in this new technological realm could not be more invigorating.